By Marina Savchenko

In the last 10 years, Russian media have changed rapidly. The process of digitalization, mobile technologies, and big data created new media landscape. Still, traditional media such as newspapers and TV remain the main information sources in the country. While the new digital tools are popular among users and journalists, what are the modern tech challenges for media in Russia?

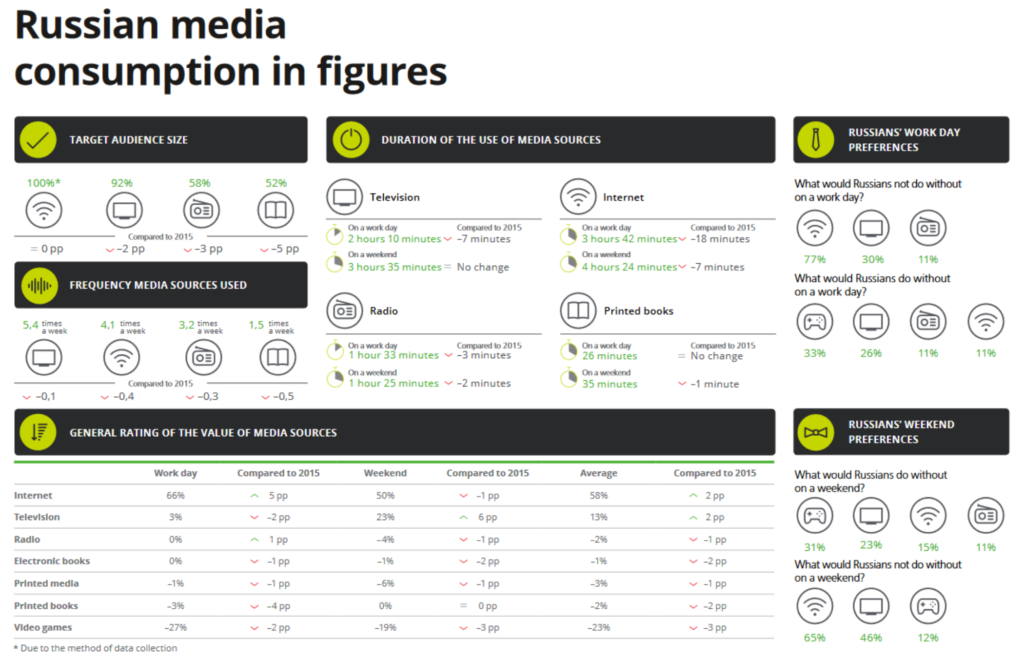

One of the tendencies of the last 3 years is the reduction of newsrooms’ sizes and focus on visual and interactive content. Print media manage to keep their audiences, and according to a 2017 Deloitte’s survey, 52% Russians read newspapers every week – making it to the top 5 media activities.

The content itself is changing; articles are not read but scrolled, so media adapt to this trend. For example, a successful Russian online platform Meduza uses the popular format called Listicle. With it, the topic is described in 5-6 sentences and answers, and it is a basis for developing glance journalism and non-click journalism. Another media trend is civil journalism via mobile devices. Media projects like Life News and Mobile Reporter use this format on a daily basis. Mobile journalism opens new opportunities for local media coverage, but there is a complexity of integrating this method in all newsrooms across the country due to phones’ technical limitations and bugs in applications.

Using mojo in traditional Russian media proves challenging; but as technology improves, journalists are starting to realize its potential impact. Bureaucracy is a part of the problem; it prevents newsrooms from innovative. Thus, while mobile footage is a well-known source, journalists usually use it only for breaking news. Most media content is produced by professional journalists with appropriate equipment.

We asked two Russian journalists, Mikhail Fishman and Anastasia Valeeva, about their experience with new digital tools and mobile reporting.

Mikhail Fishman, editor of an independent TV channel, Rain (Moscow):

“Mobile journalism represents an expansion of opportunities for journalists, especially of free media without financial support. It offers more flexibility and might be a way to cut down on expenses. Also, journalists need less kit to carry with themselves, they can produce a larger variety of formats, and have access to different places without a big TV crew. Still, it can be also challenging because sometimes you need to persuade in it editors and your fellow colleagues.

TV Rain usually uses the technique of mobile reporting because it is much cheaper and convenient. Especially with the lack of financial resources that we experience now, we switch more and more to mobile reporting. The border between professional filming and using mobile devices is getting smaller and smaller. We use Skype to interview people and mobile phones to cover events around the globe. The more we use this kind of presenting information, so more it is getting common in the new media landscape in Russia.”

Anastasia Valeeva, data journalist

Another big opportunity mobile technology provides is in investigations for data journalists. Anastasia Valeeva is a data journalism trainer and co-founder of “School of Data” in Kyrgyzstan. She has researched the use of open data in investigative data journalism as a part of her fellowship at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford. She has taught data journalism at Data Bootcamps in Montenegro and Germany, Data Journalism Summer Institutes in Kyrgyzstan and Albania, and at the Higher School of Economics, Russia. Currently, Anastasia is living in Kyrgyzstan where she works as a data journalism lecturer at the American University of Central Asia and data journalism mentor at Internews Kyrgyzstan. She has recently co-founded School of Data, public fund that aims to build active data community in Kyrgyzstan.

What is Russia’s overall position in the open data rankings?

Open data is great as long as it is used. Russia’s overall position in the open data rankings is considered to be quite high, given the political climate and compared to the neighbors in the region. The Global Open Data Index, run by the Open Knowledge International, places Russia on 38th position out of 94 countries. It is one of the two post-Soviet countries surveyed in the index, another one being Ukraine on the 31st position. If we take into account the drastic differences in the political systems of these countries, it seems surprising that the difference in the ranking between them is so small. Indeed, if we look into the datasets that are considered open, we see that Russia scores very high on opening the budget, procurement, company registers, and national statistics.

If we take a look at another ranking, the Open Data Barometer produced by the World Wide Web Foundation in collaboration with partners, Russia ranks even higher: it’s got 25th place out of 115. This is what surprised me and inspired for the research titled ‘Open data in a closed political system’. I considered it a paradox which could mean either the uselessness of the data open or the inability of the actors such as media, businesses, and NGOs to use it to its full value. My research was an attempt to evaluate the quality of the open data in Russia and to focus on journalists as the user group and their use of open data in the investigations.

Now, having done the research, I think that it is important to understand that open data alone does not equal democracy. It is a complex path that starts from the openness of the government agents, goes to the capacities of the media to produce a decent data analysis, and ends with the responsibility of the authorities and their reaction to the investigations published. Without any of those components, it is hard to put open data at work. And we should never forget that open data rankings can only tell us this much. As with every data source, don’t forget to look at the methodology: it is based on experts’ evaluations, thus, prone to human mistake.

What exactly should be done to empower and enrich investigative journalism in Russia?

In my research, I tried to bring up some recommendations for the media makers and for other agents in society. First, to tell better data stories, journalists need better data: granular, useful datasets in machine-readable format, which is impossible to achieve without the top-down initiative, but as well without the bottom-up proactive demand for the relevant datasets.

The biggest gap that needs to be closed is data literacy on all the levels, from general awareness to the data analysis skills. Here, journalists sometimes need to partner with data analysts to harness stories hidden in data. By processing the data, you can reveal patterns, check hypotheses, and hold the authorities to account on a new, digital level. This is an immense power that data journalism provides to us, and I hope media will use it.

Finally, the storytelling part is the last mile of the data journey, and we cannot overestimate the benefits of a great story that adds emotions, human element and generally, meaning to the data. Combining computer analysis with shoe-leather reporting is still a challenge for many, but it is a recipe for success.

How can new digital tools help improving investigative storytelling in Russia?

We first have to rely on the old digital tools such as Excel to improve investigative storytelling in Russia. If every journalist knew Excel as good as one can operate Facebook, we would have a completely different journalism now. Of course, new tools enable things previously impossible or very expensive – data visualization tools or data wrangling programs, such as OpenRefine, Datawrapper, or Tableau. Another thing when we talk about investigations is that journalists now can enjoy safe communications through one of several options available like Signal or pgp communications. Also, we can tell our stories in the pace and spirit of the audience – like gamification, scrollytelling, or podcasts. Still, the core of it has not changed: you need a strong story first.

We also asked Anton Lysenkov, Chief Editor at Spektr.Press, independent Russian news source based in Latvia, about his experience with new tools of mobile reporting:

Modern media trends such as mobile reporting, investigative storytelling, and access to the big data open new horizons of expression in Russia for journalists. However, this trend needs to be supported not only by journalists, but also by big media companies and media establishment.