By Sheikh Saaliq

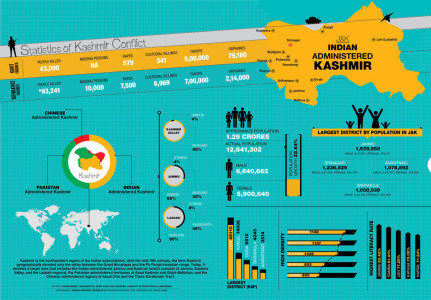

The saying, “In war, truth is the first casualty,” holds true to Kashmir. A disputed region between India and Pakistan, Kashmir has remained a flashpoint for the sub-continent for more than six decades. It is a heavily militarised zone, with more than half a million troops stationed there. Despite the ongoing conflict—which has claimed nearly 90,000 Kashmiri lives since 1990 when the armed insurgency began—the region receives very little media attention. To resolve that, alternate media in Kashmir came into force.

Many believe the rise of alternate media in Kashmir happened in 2010 when a mass movement was launched against the Indian military rule resulting in more than 120 civilian killings. During the five-month protest, the Kashmiris and those living outside the region used the virtual sphere to air their sentiments on the conflict.

As the government imposed stringent restrictions and curfew, people looked for an alternate sphere to raise their voice. Luckily, the online space proved to be a fertile ground to promote public engagement on the issue. The real news didn’t come out from the valley and so the responsibility to tell stories became all the more important.

Fahad Shah, an independent journalist from Kashmir, turned his blog into a full-fledged alternate media website called The Kashmir Walla. He says the alternate media is the medium for the people and run by the people. “It reports what mainstream media cannot report because of its limitation.”

Shah’s website came from a need to write about Kashmir for his non-Kashmiri friends who knew little of the conflict.

“We wanted these untold, unheard stories to be told and re-told. [Mainstream] media often fails to follow up few [of these] stories,” says Shah.

In 2010, the region saw a clear transition from streets protests and other forms of dissent to online. With more people gaining Internet access by using different social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter etc, stories not often showed in the past by mainstream media were covered by the alternate media.

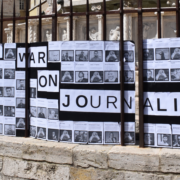

Peerzada Aaqib, a journalist who works for an alternate news magazine, The Counselor, points out the reason behind the rise of these websites. “There was censorship during 2010 and a lot of it. Newspapers were gagged and journalists were beaten. But the censorship that the Government of India had imposed on all news channels and newspapers, who were reporting from the ground, was effectively broken as a result of the proliferation of the Internet.”

“I chose to work for a platform which not only lets people tell their stories but also acts as a catalyst for healthy debate and discussion about what is happening in Kashmir,” Aaqib says.

The proliferation of alternate media in Kashmir, experts say, has happened over the past six years to narrow the gap created by attacks on fundamental freedoms such as freedom of expression, ushering the creation of a space for uncensored information.

Journalist and social activist Mudasir Iqbal believes that with alternate media, the chance of burying critical information is reduced. “Here, the power of releasing the information does not lie with a corporate,” he says.

Many websites, blogs and social media services are flourishing. Online enthusiasts in Kashmir say it is the global reach of the Internet that plays a part in them turning to the web for highlighting conflict stories.

Haziq Qadri, a part of the four-year-old website, The Vox Kashmir, believes repeatedly reporting on Kashmiri suffering to Kashmiris does not make much sense now, and that it is time to highlight these issues on a wider platform so it reaches the larger global community.

“Each alternate media outlet in Kashmir has helped the young generation move one step closer to discovering and developing themselves in the virtual world where the discourse is being dominated by the corporate media or by the government mouthpieces,” he says.

Most of the youths running these websites are passionate to the extent that they sustain the websites with their own pocket money. The enthusiastic young website owners say they may suffering on the financial grounds but are not ready to compromise in their content.

Qadri says, “Tying up with other [mainstream] organisations means that they too will have a say in the content. It increases the tendency of outsider’s interference and may lead to some compromises as well. So, this makes us hesitant of trusting anyone.”

The main selling point of these websites goes back to its content and how it is organized based on the priority given to the stories which talk about the Kashmir conflict and the daily human rights violations. These websites often cover fake encounters, stone pelting incidents and civilian killings by the forces, which more than often are being neglected by the mainstream media. What the mainstream may put on their inside pages, alternative media puts up front on the website. Work culture in most alternative media websites is informal; there is no tight editorial control and disagreements are common.

Adil (name changed), who runs a satirical website which mostly runs critiques on the government believes that the political narrative in Kashmir has changed since the emergence of alternate media. He believes that more and more people are coming out with their voices, which was not the case before because of the state censorship, continuous crackdowns on the information and media surveillance.

“The set notions about Kashmir and the people of Kashmir have been changed. In India also, the discourse set by the mainstream media is being challenged and this is all because of the alternate media,” he says.

These alternate media websites are presenting people’s narratives and are challenging a hegemonic control of information, which is contrary to the mainstream Indian media houses.

Qazi Zaid, a freelance journalist whose work has been featured in FirstPost, Kashmir Life, The Kashmir Walla and others, believes that alternate media is a must in a conflict zone like that of Kashmir.

“If you know how alternate media is helping to build the case for Palestine cause, you’ll understand the need of alternate narratives. Also, there are so many hidden stories and events which need to come fore and alternate media is doing that,” Zaid says.

Paramita Ghosh, a journalist with the Hindustan Times, who has extensively reported on the alternate media in Kashmir and India, believes that the inception of these websites is because of the lack of the counter-narrative. She says many of the events that happened in Kashmir during last 25 years, grave human rights violations, and the rise of a new and alternative model of journalism are closely linked

“These websites not only have given people a vent to share their political ideologies but steadily developed into important forums of public debate and discussion. Stories which were hidden all these years have started to surface. People are writing and discussing,” says Ghosh.

But being ‘alternative’ comes with its own work pressures: the daily hustle of presenting news at an angle different from the mainstream, the job of keeping up the commentary in periods of lull when most of the news is either being filtered by the state or being completely gagged, and most of all, to change the perception and processes of news-making.

Right now there are almost ten alternate media websites in Kashmir most of which are being run by freelance journalists. Mostly trusted by the public, these websites are a source of first-hand information regarding different daily events happening in Kashmir.

With the lack of funds, manpower and state repression, the future of these alternate media websites may seem draped in an uncertainty but most of the owners of these websites believe that the “urge to report the truth” will still remain a catalyst for them in operating these alternate news websites.