By Una Kelly

The lights go down, the hum of conversation fades, and the music begins. Derry City in Northern Ireland is no stranger to cultural celebrations in recent years – in 2013 it was named UK City of Culture. But this open mic event on a late afternoon in winter has a distinctly foreign flair. The snacks are falafel and baklava, the stories and lyrics are in Arabic.

It’s the grand finale of the Sharek project, a ten week programme of cultural workshops delivered by Syrians and other Arabic speakers for the local community, funded by Derry City and Strabane District Council. The evenings of food, poetry, singing and dancing are the brainchild of Jo Bird, who manages the project along with local theatre company Sole Purpose Productions. “Grassroots organisations are hugely important,” says Bird. “The statutory authorities do what they can in terms of accommodation and paperwork, but we also wanted to provide an opportunity for people to interact and make friends.”

- Arabic Cafe’s organizers. Left to right Fadl Mustapha, originally from Palestine, Pat Byrne of Sole Purpose Productions, and Jo Bird. Copyright Rik Walton

- Asem Sweidan, bilingual support worker at North West Migrants with dance partner Caroline at Arabic Cafe. Copyright Rik Walton

The turnout at events grew over the months the project was running and involved around three hundred people. More than fifty Syrian refugees arrived in Northern Ireland in April last year, and many of them got involved with the workshops, teaching music, art, language, and cooking Middle Eastern food. They had fled from a homeland ravaged by war, and began to make new lives in a country still healing from the scars of its own conflict – Derry was the scene of many tragedies of neighbour pitted against neighbour during the period of sectarian violence known as The Troubles.

“Derry is not very multicultural. It’s more bicultural,” says Bird. “There’s a strong Catholic and Protestant divide, and that’s been one of the unexpected gifts of this project. It’s brought the existing communities together.” However, as Bird assures, the project does not focus on assimilation. “It’s not about us telling them how things are here,” she explains, “Integration is a two way thing, it’s also about adapting to newcomers.”

- Some of the food cooked by Syrians for the Arabic Cafe event. Copyright Sole Purpose Productions

- Syrian man Hasan Hasan (right) tells a story with the assistance of Fadl Mustapha (left). Copyright Rik Walton

There’s laughter, there’s song, and many of the refugees speak about what a warm welcome they have received. But other thoughts weigh on their minds. Through a translator, Fatima tells of her struggle to reunite her family, who separated when fleeing the war. Her blind son left Syria before the rest of the family with the assistance of smugglers. She says he ended up in Germany while the rest of the family eventually came to Northern Ireland – but because the son is over eighteen, it will be incredibly difficult to be reunited with him. They talk a lot over the phone, Fatima says, but they cry more than they talk.

Securing work has also been difficult – but they hope that may soon change for some of the refugees. The most popular events of the project involved food, so it was decided the first Arabic Café should be founded in Derry. Some of the Syrians, with the assistance of local people, have begun looking for suitable premises and training in certified food preparation.

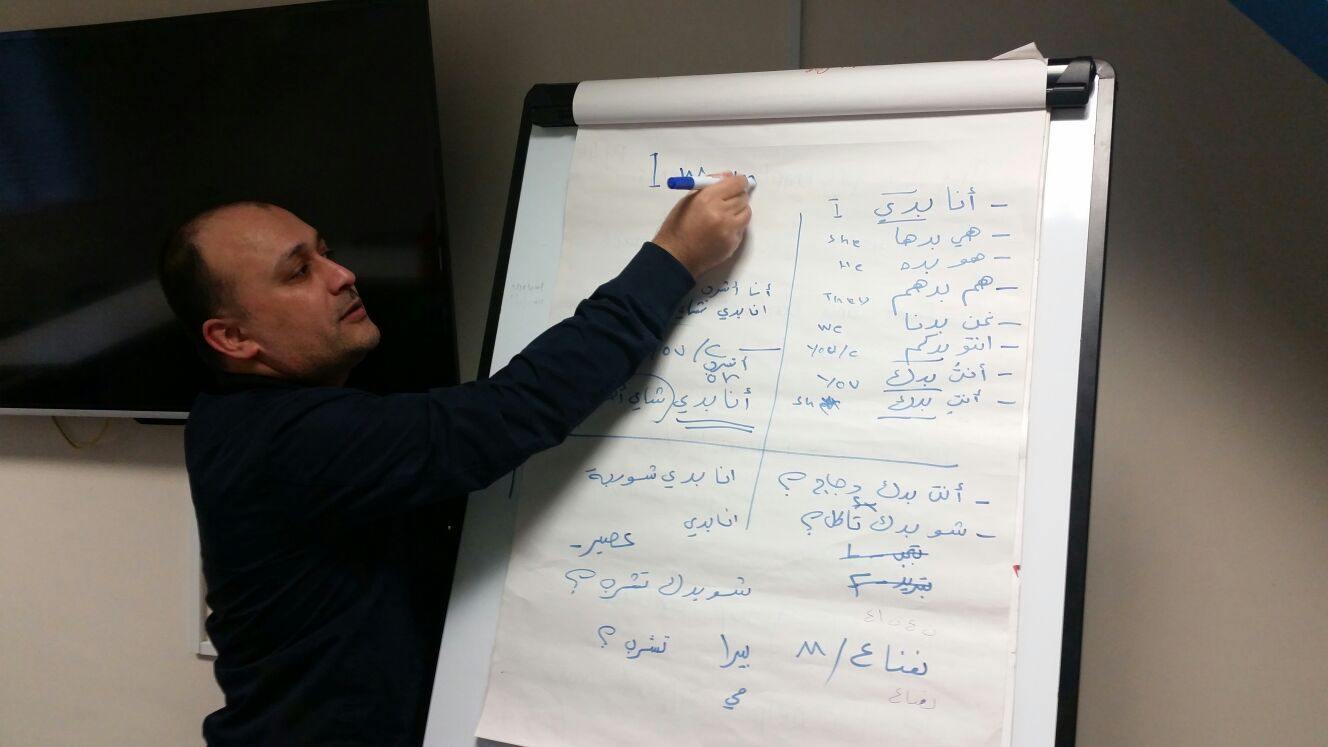

Arabic language classes are also a legacy stemming from the project. Syrian journalist Rami Zahra arrived in Derry in April last year. He teaches weekly classes in beginner and intermediate Arabic. “It’s a beautiful feeling when Derry residents ask you to teach them your language. Arabic is one of the richest languages in the world, with more than twelve million words,” he says.

- Syrian journalist Rami Zahra preparing the Arabic class. Copyright Una Kelly

- Left to right: Doherty, Bird, & Zahra at Arabic classes. Copyright Una Kelly

The classes are an example of how local people benefit from the new arrivals in town. Audrey Doherty is interested in Middle Eastern dance and wants to learn Arabic to convey the lyrics of the music she dances to. Doherty used to live in London and couldn’t find suitable classes there, so she was delighted to now find them in Derry. Asked if she thinks other communities could take any tips about integration from the projects here, she nods her head vigorously.

“People could absolutely learn from what’s happening here. It’s a cultural exchange, we learn from it, and it’s important for local people to dispel the fear around Islam,” Doherty says, “It’s important for the communities to integrate because the fears are based on myths.”

Jo Bird agrees. “Well functioning societies have always welcomed newcomers. Isolated societies can be damaging,” she says. “Each particular place has to figure out what’s right for their area and the people there – and we’re happy to talk to people about creative integration projects in their communities.”