The Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia has collapsed. Two million people died due to their genocide. How to judge the executioners?

“If we killed people… and I personally killed people… and of our own free will, then that‘s evil. But I was given orders. They terrorized me with their guns and their power. That‘s not evil. (…) Ever since I was a child, I have always been good. I still am today. I don‘t steal or do holdups, I don‘t hurt anyone.”

Hell Reigns

In Cambodia reigns hell: schools closed, currency abolished, religions banned, forced labor camps, surveillance, famine, terror, executions. There is genocide. Two million dead. It‘s the Khmer Rouge and it‘s what Rithy Panh’s documentary is about.

Feeling the shame

Watching movies like this one, we shake our heads in disbelief. How can a man cause so much pain and suffering without blinking an eye? Where does his cruelty come from? We all agree that the torture depicted in the film and the personal tragedies shown onscreen are unbearable. We agree that a human being should never be exposed to such trauma. The present situation of victims, of the few who have survived, is clear. We sympathize with them. When Chun Mey, the former prisoner of the Khmer Rouge regime, breaks into tears while standing in front of S-21, the most famous and probably the most savage interrogation center in the world, where he had been imprisoned, we feel like comforting him. We feel his shame as we watch him become unable to control the stream of violent emotions brought on by painful memories. We feel uncomfortable as we stare at him weep over his murdered family and bemoan his ruined life. The more the details of the atrocities perpetrated by the soldiers are described, the more furious we become. We want to shout out and condemn the executioners.

Those who contributed

But who are they? Where are they? If the case of the victims is clear to us, if we know what to think about their past and present tragedies, the situation of their torturers is not so simple. We imagine they look dangerous, with hate in their eyes, clenched fists, and a gun. We hear them claim that they are proud of torturing and killing people. Isn’t it easy to condemn them this way, to find them guilty? But reality is not black and white. Those who contributed to the Khmer Rouge look a lot like the victims. There are no hateful eyes, no pistols in their hands. They justify their cruel deeds with their fear. “I was given orders. They terrorized me with their guns and their power,” one former oppressor explains.

Lousy lifes, violent deaths

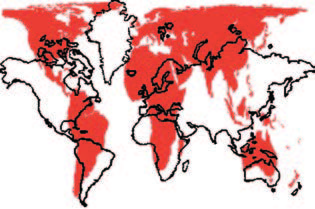

It doesn’t matter, one may object. Killing is killing. So easy to say from a comfortable armchair, in a safe home, isn’t it? But what would you do if a loaded gun was held to your head? What would you do if saying ‘no’ meant certain death? World history knows hundreds of stories about the choice between a lousy, immoral life and a tragic, violent death. Let us examine the Holocaust and the German concentration camps. Probably each nation of all those represented in this World War II killing machine has its own heroes – those who not only refused to cooperate with the Nazis by reporting on other prisoners, but those who in fact openly disobeyed them. They usually paid for their courageous acts with their lives. But a lot of very different stories exist as well. Sad testimonies about the dark side of the human soul. Because people stay civilized as long as they are surrounded by a civilized world. But when the situation changes, when the system of values and morality is turned upside down, they can no longer live like they used to. And then some people break down under the burden of the new cruel reality. Treated like animals, they start acting like animals. Brutality becomes their new face. Do we have a right to judge them?

Especially if they were children, like those Cambodian prison guards indoctrinated at the age of twelve or thirteen. How much do we know about life and its traps, even in a time of peace, as teenagers? “My son never behaved badly, never insulted the elders. But they indoctrinated him, turned him into a thug who killed people,” cries a mother of one of the jailers.

How to judge them?

If we stopped here, maybe we could even feel sorry for those poor Asian children forced to brutalize the “enemy,” that is, to rape women, beat their husbands and murder their babies. But, again, that would be too simple. Let’s assume that they were doing all of this, but deep in their minds they knew that such behavior could be only temporary. The civil war is over, the regime has collapsed. Life in Cambodia is changing slowly. We expect the ex-torturers to expiate their guilt, at least to confess to their sins and apologize for them. To take some responsibility for what they have done. But those shown in Rithy Panh’s film don‘t do anything of the sort. They seem to have no remorse. There are moments when they look mildly ashamed by the questions asked of them, but after a while they show emotionlessly just how the prisoners were treated. They describe with detail the crimes they committed. They even act this way while talking to their former victims, displaying unusual, unbelievable self-confidence. In theory, we could defend them and say that Rithy Panh, the film director, whose sisters and parents were murdered and who himself had been sent to a labor camp, will never be objective. We could, if only we had the slightest impression that the film was not an honest appraisal but a one-sided view showing only single episodes of the Khmers‘ unaccountability. But my impression was exactly the opposite…

The only question that remains is how should we judge them if one day they say they are sorry.