By Anna Romandash

False news is no longer news; at least, in the literal sense. Most Europeans have, at least, heard the term, and even if they do not know the exact meaning, the knowledge is there. Yet, is it enough to know about false news phenomena to resist fakes? The short answer is no, especially in the countries most vulnerable to it.

Among the biggest false news targets are Central and Eastern European states; while some have joined the EU or have strong pro-EU aspirations, there are countries that deteriorated to nearly totalitarian state, and where media are strongly controlled by the government. While these states lack free journalism, most countries in the Central and Eastern European region are affected by the Russian fakes due to lack of effective national response, fewer resources, and weak civil society.

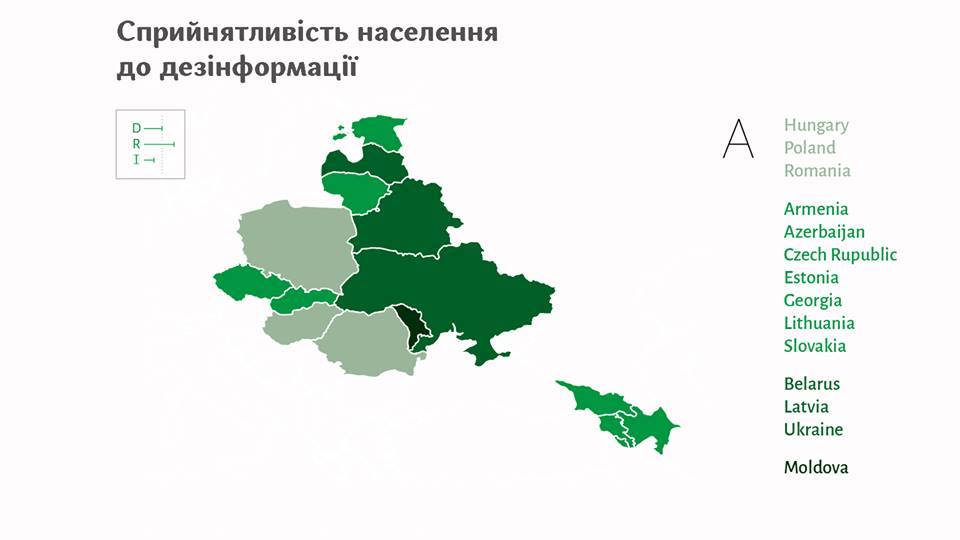

According to the Disinformation Resilience Index, a research by “Ukrainian Prism” Foreign Policy Council and EAST Center, Russian fake news was still a big influencer in the CEE region. The research, conducted from May 2017 until May 2018, has collected data from Visegrad and Eastern Partnership countries as well as Romania. The research analyzed how different countries respond to the false news produced by Kremlin-related news organizations, and whether societies and official institutions were able to provide an adequate response. While there are regional differences, most countries struggle when it comes to dealing with fakes.

“In Central Europe, Russia does not use one common strategy. They are very particular, very cunning, trying to peak the weak points and influence them,” says Volha Damarad from the East Center, who has been part of the research team. In other words, propaganda and false news targeting audiences across countries differ and appear in various formats and through diverse media. This creates a vision of credibility as information comes from many platforms, and it often focuses on topics that do not match in neighboring states.

While there are many reasons for different approaches when it comes to propaganda, the amount of minority groups – especially Russian ones – across the countries as well as country’s outreach and involvement with these groups is an important factor for Russia’s fakes to work. In countries where Russian minority groups are large and noticeable – such as Latvia or Belarus – these communities are the most prone of risk to believing in fakes and spreading them around. However, it is important to add that the communities go beyond ethnicities; rather, we are speaking about groups whose main language of communication is Russian, so they are most likely to get news from Russian-language sources. Age plays a significant role, too – older generations and people who have experienced living in Soviet Union or Eastern Bloc are also more vulnerable to information attacks.

“Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova are the most vulnerable to disinformation,” says Hennadiy Matsak of “Ukrainian Prism”, “Research once against proved Kremlin’s strategy to keep buffer zone in Eastern Europe.” While neighboring countries are also exposed to propaganda, its influence is smaller firstly because of fewer Russian speakers, smaller quantity and impact of pro-Kremlin media, and fewer ties with Russia when it comes to history, society, and economics. What all states do have in common – with an exception of Lithuania – is the lack of a systematic national response to the information threats and no clear strategy on how to battle Russian fakes. While there are new organizations appearing, they seem ineffective in providing a constant response, and local media institutions that are supposed to monitor and regulate news organizations also fail to counteract propaganda. More importantly, Kremlin-backed organizations manage to operate within national legal systems as they find faults in the laws and officially hide their affiliation or main aims.

While responding to propaganda has been mainly a failing act, mostly due to a lack of a governmental strategy, there are tools civil society can use to battle false news occupying information space. Among them are good old quality journalism and checked facts, but not only. Fakes can be approached through offline events and activities, which aim to educate society and provide them with critical media literacy skills. This is easier said than done, especially in pseudo-democracies like Belarus and Azerbaijan, where non-governmental actors are either weak of pressured. “Democratic values cannot be protected in a society with undemocratic instruments and mechanisms,” says Guram Ananeishvili from Foundation Liberal Academy in Tbilisi, “We have to work closely with civil society to activate government against common threat.” Thus, to address the problem of fakes, larger issues have to be challenged first – such as democracy at stake and education and culture it promotes.