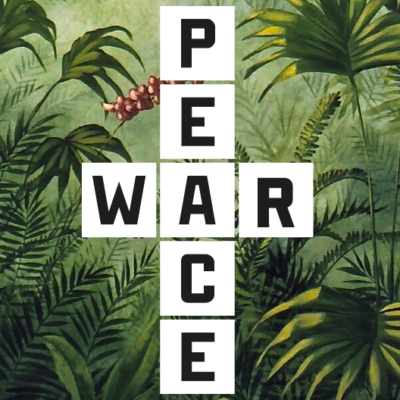

Ever since the outcome of the Paris Conference up to the contemporary rise of independentist movements in Europa and across the world, the question of self-determination and its practical application in political communities remains a major point of contention. The Orange Magazine visited the “Good Peace vs. Bad Peace” workshop at the “War or Peace?” festival in Berlin in order to dive deeper into the issue of self-determination and to report on how the many participants relate to the topic.

To begin with, the workshop was provided by the European Association of History Educators (EUROCLIO), which represents an umbrella association of more than seventy history, heritage and citizenship educators’ associations. With the support of Prof Robert Stradling, Prof Ute Ackermann Böros and Agatha Oostembrug, many young people from all over the Globe had made their way to Berlin to learn and to discuss self-determination and above all the matter of peace. People came from Kosovo to Georgia and from Turkey to Serbia to reflect on the multidimensionality of the problem, between the narratives of clash and the narratives of unity, between exclusion and inclusionwithin and across the borders which cut through the maps of Europe and beyond.

Some of the many case studies were for example the Paris conference, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the process of de-colonisation. What all these events have in common are their historical continuities and divergences in the application of the right to self-determination. The dominant finding of the workshop was the importance of historical narratives of self-determination processes in current times, which is fed by the significant role of public and civic education. Orange Magazine had the chance to deepen the discussion about education and self-determination in a conversation with the teamers of the workshop.

Orange Magazine:Which role do historical events of the 20th century, such as the Paris Conference, the Skykes-Picot agreement, and the dissolution of major empires, play in relation to self-determination?

Prof Stradling: Today, self-determination is a human right along with other human rights, but who has the authority to decide on a shift of borders? One thing we learned in the last 100 years about the great powers is that they put stability above all other things.

Prof Ackermann Böros: I think, generally speaking, the agreements are a great stone of contention. The question is whether the people who live in the countries which are actively involved in issues of self-determination, should still refer back to these declarations or should they rather look ahead and see where we go from here.

Orange Magazine: The sub-title of the conference reads crossroads of history; do you think international politics is at a crossroads right now, just like 100 years ago?

Prof Stradling:We are slightly moving back to a situation which seems more familiar to the Cold War than the situation in 1918 and also 1914. Realpolitik still dominates the international scene with issues, such as the Kurdish question, which present us all with a great dilemma. Ultimately, they do show how realpolitik cuts across people’s legal rights, human rights. In terms of narratives, history is often selectively bent at the service of certain politics. They tend to be over-simplistic. It is important for a historian to portray differences and continuities if we want to avoid making the same mistakes over and over again. Nonetheless, one shouldn’t make the mistake of drawing simple analogies, history is never identical.

Orange Magazine: The revolution of new technologies, illustrated best by the rise of social media, seems to create more polarization rather than reconciliation. How could technology and particularly education play a positive role in this challenge?

Prof Ackermann Böros: The latest EUROCLIOproject is called “learning to disagree”, and I think that’s a particularly interesting direction to be moving in. It’s a recognition that the discourse on social media leads to a lot of simplification. We need people to disagree, but also, we need them to sit down together and discuss their disagreements. This requires analyticaland critical skills.

Prof Stradling: Take the example of fake news. Ernest Hemingway used the interesting phrase “we all need a built-in crap detector” and I think this is one of the big things that education should be doing and also what EUROCLIO aims at. The skill of media-competency becomes indispensable in current times.

OrangeMagazine: What do you wish for participants to take back home from this workshop and maybe from the conference?

Prof Stradling:I would imagine that people who join this conference, when they go back to their country, will become people who are mobilizers in society. Mobilizing their own generation. Perhaps not to wave flags and join political parties, but that they go out there and start saying, “it doesn’t have to be like this”.

Prof Ackermann Böros: I see a whole generation of university students who are relatively politically passive: they are worried with their own career, finding the money to pay for their fees. As a result, politics doesn’t really matter to them. But it doesn’t have to be like that.

by Francesco Lanzone