Text by Irene Dominioni, Italy

“How much news is fake news?” asks Damian Tambini, Associate Professor and Director of the Media Policy Project at the London School of Economics, during his speech at the Summer School “Journalism in the Digital Age: responding to propaganda and fake news” held this month at the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) in Florence, Italy. From the pie shown at the beginning of his presentation, according to a research conducted by the Boston News Institute, of all news stories shared on Facebook, more than 25% is actually fake. A figure that appears enormous.

“Now, as you might have suspected, that research is completely invented. My 15-year-old daughter made those slides in about five minutes” says Tambini, turning to another slide picturing a young girl behind a laptop. An embarrassed chuckle crosses the room, populated with young journalists, students and media researchers from all over Europe.

“Today it’s quite easy to make up things that look real”. Fake news is not something new as a phenomenon, but, according to Tambini, “something has changed”, making the circulation and resonance it is having these days much more worrying than in the past.

First of all, the profitability of fake news has changed: insurgent populists have a lot to gain from it, because being allowed to label large parts of public discourse as fake represents an advantage. There has also been a change in the distribution and advertising system of the news: companies are now buying clicks and views, not space on a page or minutes on TV, therefore pointing out a need for catchy titles and content.

Also, the viewability and shareability of stories has increasingly become crucial, overshadowing the validity of content; and finally, there has been a structural change in media systems, threatening traditional journalism and pointing out the entire question of the quality of information even more strongly (not as much as 25% of news shared on Facebook is fake, but there is definitely a big deal of wrong information circulating on social media, says Tambini).

What should be done about fake news? In terms of policy responses, there have been calls for new legislation in Italy, Germany and elsewhere. In the case of Italy, in February 2017 a group of MPs presented a law proposal named “Regulations to prevent the manipulation of online information, guarantee web transparency and incentivise media literacy”. The draft contained possible measures to contrast the unrestrained spreading of hoaxes and misleading news by establishing pecuniary fines and criminal sanctions. Specifically, the draft foresees a fine up to 5.000 euros against those who spread news that are “exaggerated or biased, regarding facts evidently unfounded or false”, and a 12-month imprisonment for those who disseminate “news that cause public scaremongering or harm to the public interest”.

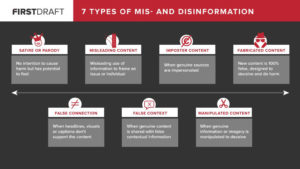

The vagueness of the definition of what the proposal considers fake news led to strong critique from all sides, identified as a threat to freedom of expression, and defined “dangerous”, “unrealistic” and “useless”. Indeed, the concept of fake news is complex, and has been identified as both “falsehood knowingly distributed to undermine a candidate or an election; falsehood distributed for financial gain” (the case of the Macedonian town of Veles became big during the American elections), but also bad journalism and unsubstantiated humor (such as that of tabloids). New forms are also encountered in whatever news is seen as ideologically opposed or challenging consensus – and therefore labeled as fake, the way Donald Trump does recurrently – and parody.

The proposal for fake news law in Italy was also criticized for its aim to regulate blogs and other websites in the framework of “editorial responsibility”: the obligation for every website owner to register their domain by the public authority (similar to the way newspapers do), and also to remove contested content within 48 hours appear inconceivable solutions to the issue of fake news, creating more problems than they can actually solve.

Tambini agrees, and addresses the law proposal that was presented to the Parliament as “dreadful” and reminescent of an Orwellian kind of reality. Interviewed by Orange Magazine, he said: “When you have definitions of what is fake news or inappropriate content that are too wide, and you give the right to a governmental agency to decide what is truth and what is fake news, that can have a very direct and worrying censorship effect. The last time I looked at the Italian proposal, I thought it was dangerous, because to me it meant moving towards some kind of Ministry of Truth, which completely goes against the established democratic traditions. If we establish this kind of agency, it is almost inevitable that it will be misused.”

The question of establishing what is truth and what is fake in the first place is a complex matter, dealing with philosophical as well as practical dimensions, which the law proposal hasn’t successfully outlined. Nevertheless, there is a positive aspect to this law, Tambini observes. The reference to media literacy and tools to support it is acknowledged as one of the most important elements in the fight against fake news, democratically providing to everyone the skills to distinguish the reliability of sources and use the Internet wisely and effectively. This is one of the respects where legislation can help in a substantial manner, by promoting specific programs and devoting resources to it, adds the scholar.

What else do we need? According to Tambini, a lot of the responsibility rests on journalists and media organisations’ own shoulders: “We need more public awareness, self-regulation and support for independent journalism, rather than any censorship approach. We don’t have regulation of the press; we have self-regulation, journalism ethics and quality professional journalism, and we let the journalists decide what is true”.

In other words, the press needs to be free, this being the most basic democratic requirement for a healthy and well-functioning media system. Keeping in mind that “journalism is not free speech”, as Chris Elliott from the Ethical Journalism Network stresses during his speech at the CMPF Summer School, codes of conduct for journalists are evolving and will increasingly need to do so, in order to meet new levels of trustworthiness. Reputation, accountability and reliability will make a difference in deciding who has the power to speak and to decide what is true. At the same time, the need to create new generations of responsive and resilient news consumers, who are able to critically evaluate and utilize news, will increasingly become crucial to improve the media environment. Will that be enough? An opportunity for exchange on these themes is coming up at the Deutsche Welle Global Media Forum, taking place in Bonn, Germany, between June 18-21st, where the questions of how to rebuild media trust and increase media literacy among the public will be discussed. And, perhaps, some answers will be found.